When Andrea Dworkin Told Pedophile Beat Poet Allen Ginsberg She Wanted Him Dead

Pedophilia and the “+” in “LGBTQ+”

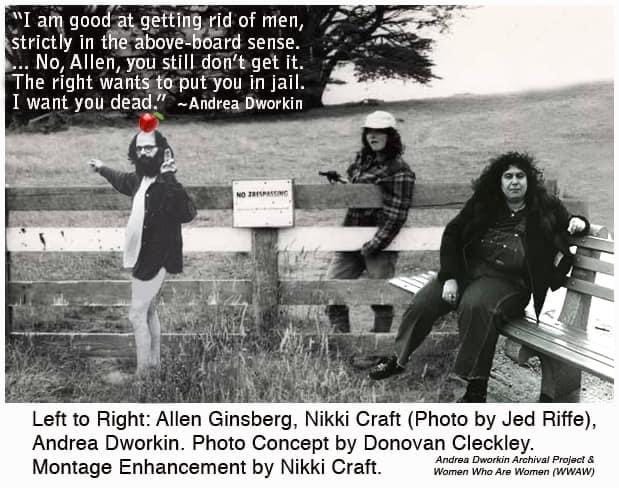

The following introduction and transcript, with the accompanying image, appeared on the Andrea Dworkin Archival Project. It originally appeared on May 9, 2023. Nikki Craft and Donovan Cleckley thank The Distance for reprinting the piece to help share the archival work we have been doing.

Introduction

By Donovan Cleckley

No, Allen, you still don’t get it. The right wants to put you in jail. I want you dead.

- Andrea Dworkin

Though we did not plan it, after continuing edits and work on the audio and its transcript, this reveal has landed on its anniversary. In this conversation, recorded exactly thirty-three years ago today on May 9, 1990, Andrea Dworkin and Nikki Craft discuss the sexual abuse of children. Their discussion names the abuse carried out by Allen Ginsberg, always Whitmanesque—and pictured as “the great poet.” A supporter and member of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), Ginsberg objected to a constitutional law criminalizing the possession of child sexual abuse materials. He claimed that the law infringed on his rights and his freedoms pertaining to a “love” for boys, ones as young as thirteen. “I’m a member of NAMBLA,” Ginsberg said, adding, “because I love boys too—everybody does, who has a little humanity.” But whose humanity, really?

When he encountered her right before their godson’s bar mitzvah, Ginsberg cronfronted Dworkin about how persecuted he felt over the criminalization of child sexual abuse materials. He refused to take her “No” for an answer and pursued her, in vain, likely presuming that he could persuade her to comply with his desires, if not explicitly affirm them. “I made clear to him, from the first time that he brought it up,” Dworkin said, “that I was on the other side of this and that I regarded this as child molestation and nothing else.” In Heartbreak: The Political Memoir of a Feminist Militant, Dworkin’s 2002 autobiography, she recollects this encounter with Ginsberg. The Supreme Court had just ruled child sexual abuse materials illegal. She writes:

I was thrilled. I knew that Allen would not be. I did think he was a civil libertarian. But in fact, he was a pedophile. He did not belong to the North American Man/Boy Love Association out of some mad, abstract conviction that its voice had to be heard. He meant it. I take this from what Allen said directly to me, not from some inference I made. He was exceptionally aggressive about his right to fuck children and his constant pursuit of underage boys. (p. 38)

During her conversation with Craft, Dworkin discusses what she terms “pedophile logic.” The argument used eighteen years, minus one month, and so on, to posit a kind of age fluidity. Age seemed nothing but a number to him, a boundary to be stretched and, if possible, broken. “He changed the subject, without saying he was changing the subject,” she said, “to having sex, not taking photographs.” Ginsberg alternated from eighteen, seventeen, and sixteen to using the boys at the bar mitzvah as examples. “He pointed to the friends of my godson and said they were old enough to fuck,” Dworkin writes, “They were twelve and thirteen. He said that all sex was good, including forced sex” (p. 39). Reasonably, then, she wanted this conversation to end, but he insisted on his rights and his freedoms. Their exchange culminated with him believing Dworkin wanted him jailed by the right, persecuted for his so-called “love” of boys.