Change Artist: One Man's Long, Strange Trip Around the World in Search of His 'True Self'

A tale of modernity and 'authenticity'

“Two strains of mind and action have always been in conflict in my life,” Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln wrote in the opening of his dubious jailhouse memoir, Revelations of an International Spy. “In one of them predominates the quiet fervor of the mystic and the imaginative sensitiveness of the artist. In the other, craving for excitement, passion for deduction and analysis, and love of applause overshadow all other leadings.” The year was 1916. Styling himself “a diplomatic spy,” the 37-year old Hungarian-born Trebitsch Lincoln had been arrested on charges of forgery, and was fighting extradition to the United Kingdom, where he was wanted on charges of fraud. As the United States had no domestic law against espionage against third party nations within American borders, fraud was the charge that London could use to extradite him.

“My desire is to bring home the guilt and responsibility for this war to its real authors,” he claimed in the New York World Magazine, echoing populist antiwar narratives down the ages. “The English people, as such, are innocent. They surely did not want the war.” He was ready to name names. “In the following pages,” Trebitsch Lincoln promised, “they and the world will learn for the first time who dragged them into this war and why.” He then named the late King Edward VII and his advisers in a serialized screed against “the hidden moves on the international chessboard” by powerful interests acting in secret. Trebitsch Lincoln had learned the details of the “conspiracy on foot” from a “cryptic Scot,” he said, and confirmed them during his five-year career in “Secret Service work.”

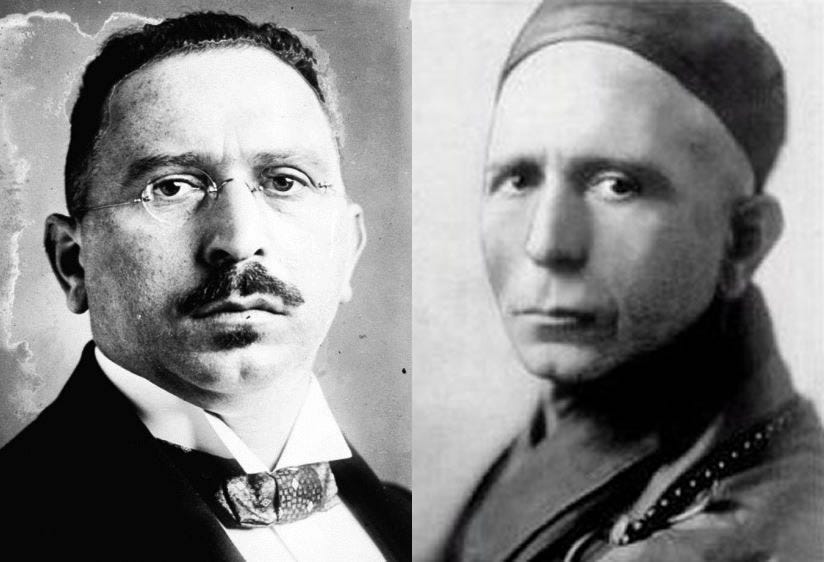

It was all baloney. Fast-forward to October 1943, when Trebitsch-Lincoln died in Shanghai as ‘Abbot Chao Kung,’ a Buddhist monk and cult guru with his own monastery and a European evangelizing mission. The circumstances of his death are murky, but we know from The Secret Lives of Trebitsch Lincoln, a 1988 biography by Bernard Wasserstein in History Today, that the attendees at the funeral were “a cosmopolitan crew” that “included senior figures in the Chinese Buddhist monastic hierarchy, various European expatriate advernturers, an agent of the Japanese Kempeitai (secret police), and the chief of the Gestapo in the Far East.” His development as an enemy of the British Empire blossomed into holy war. His mysterious end in Shanghai “reflects the larger travail of a whole new world on the road to nowhere,” Wasserstein writes. In the pay of Axis powers at the end, Trebitsch Lincoln had “thrust his services upon his employers.” Yet he “cannot be categorised as an ideological Nazi. In the last resort he was not really a patriot for anybody — except perhaps, towards the end, for his twisted concept of Nirvana.”