Conservative Men in Conservative Dresses: The Article That Described Today’s Trans Movement Over 20 Years Ago

This perceptive piece was a portent of problems in the present

In April 2002, The Atlantic published an article by American writer and psychotherapist Amy Bloom titled “Conservative Men in Conservative Dresses: The World of CrossDressers Is for the Most Part a World of Traditional Men, Traditional Marriages, and Truths Turned Inside Out.”

The article has since disappeared from The Atlantic archives, even though Bloom expanded it into a book, released that same year, called Normal: Transsexual CEOs, Crossdressing Cops, and Hermaphrodites with Attitude.

Thankfully, it has been saved in some places, including on the website Children of Transitioners.

What’s fascinating about Bloom’s piece—and why it merits preserving as well as continued attention—is that the cross-dressing men it describes are essentially the “trans women” of today.

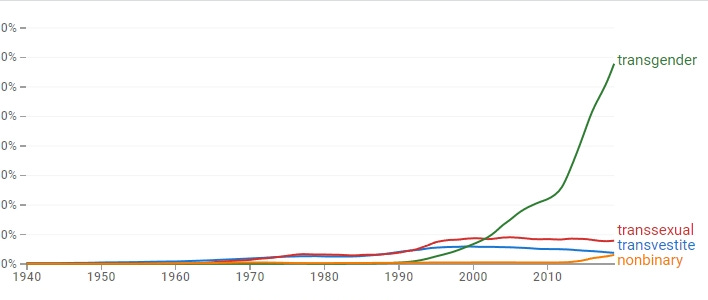

If you’re involved in the gender ideology debate, you might have heard the phrase, “where have all the cross-dressers gone?” The question is often rhetorical and meant to point to the idea that most of them identify as trans now.

“Heterosexual cross-dressers bother almost everyone,” Bloom begins, and it’s hard to argue with her.

She continues: “Transsexuals regard them as men ‘settling’ for cross-dressing because they don't have the courage to act on their transsexual longing.”

I would like to point out here that many of the types of men who cross-dress—namely, heterosexual men—have also always made up a sigificant portion of “transexuals.” However, the popular imagination usually assumed that transexuals were effeminite homosexuals.

Regardless, many more men who, in 2002, would have identified as cross-dressers, are today emboldened by gender ideology to view their sexual fetish as a sign that they are really women. And many more people have fallen for it.

Consider this passage that is so reminiscent of the stories of so many “trans women” and their trans widows today. Simply replace “cross-dressers” with “trans-identified men” and you have a story that is playing out in many relationships where a man “comes out” as trans later in life.

Many heterosexual cross-dressers never come out of the closet, not even to their wives. Others tell their wives after ten or twenty or thirty years of marriage, sometimes because they've been caught wearing their wives' clothes, sometimes because the clothes have been discovered. (The revelation that a man himself is the "other woman" is a staple of cross-dresser histories.)

Bloom also highlights the compulsion that these men have to take their fetish public, writing: “Lots of these men, driven by loneliness, by unmet narcissistic needs (all dressed up and nowhere to go), by risk-taking… want to cross-dress outside their bedrooms.”

And so, she describes how they organize get-togethers where they can be seen, including conferences and cruises. The wives often get dragged along, and she describes them as “simultaneously objects of much public appreciation and utterly secondary to the men's business.”

What an excellent way to describe the relation of actual women to many of the men who claim to be women today: utterly secondary to the men’s business.

Consider, as well, how accurately the following sentences describe what today’s trans-identified men ask of their wives and even from the rest of society:

Cross-dressing is a compulsion, but we must not see it as a sickness. A good wife should tolerate it because the man has no choice, but it isn't too hard to tolerate because it's a gift. It is about fun and pleasure--and it's a necessity.

The reason that what Bloom observed of cross-dressers in 2002 maps so neatly onto what we are seeing of “trans women” in 2023 is that these men are usually autogynephiles: they are aroused at the idea of themselves as a woman. As their claim to femaleness is based on male sexual arousal, it bears absolutely no resemblance to the experience of actually being a woman.

This is exactly what Bloom noted in an interaction with a man named Jane Ellen, the chair of a cross-dressing group known as Tri-Ess:

Jane Ellen told me, "Men are still being trained--well, you know, as Virginia Prince [the founder of Tri-Ess, and one of the godmothers of cross-dressing] says, ‘Men are always trying to become what women are content to be.'"

"What is it that women are content to be?" I asked.

"Oh, you know, they know when to give it a rest. They know when and how to quit. They can relax and be themselves."

I did know. He meant that in his vision, idealized and old-fashioned, women are like oceans, or like fields, or like horses, and men are sailors, farmers, and cowboys, and that is their curse and that is women's blessing, although women may not realize it. It is exhausting to be a man, and delightful to kick off those demands and slip into something more comfortable.

Bloom’s is a natural reaction virtually all women would feel to a man telling us that we are “content” to give it a rest and relax, to simply be ourselves, and that men don’t have such a luxury.

The article continues:

"A lot of men, myself included, want to go there, to be a feminine self, to slow down and stop striving," Jane Ellen told me.

"It sounds like yoga," I replied.

Jane Ellen was silent. It sounds like yoga except for the two hours of preparation time. It sounds like yoga except that it begins in a man's life as an erotic response and becomes an erotic fetish. Sometimes I put on lipstick when I'm tense. It makes me feel armored, less vulnerable to the world. That's not the same thing. I don't feel that the lipstick is essential to my being, that without it I must stay home.

As part of her research into men who think that being “feminine” means to stop striving, Bloom joined some of them on a Carnival cruise to Catalina.

While on the cruise, she observes that the men, who she initially assumed had copied their fashion sense from their mothers—"Hence the heavy foundation, the blue eye shadow, the big pearl-button earrings”—were actually borrowing their look from their wives. Today’s “trans women” very often do the same.

At one point, a Southern Baptist minister calling himself “Felicity” remarks to Bloom, “I’d say you pass pretty well.” He looks down at her pants and continues, "you gals just get to cross-dress all the time and no one says boo."

Bloom poignantly captures the thinly veiled narcissistic rage many trans-identified men exhibit when their illusions are shattered:

He sounds furious that life is so easy for me and so hard for him, but because he is a minister, and even more because he is dressed as and representing someone named Felicity, he cannot be direct or angry; he has to try to convey a serene and gracious femininity regardless of his feelings.

And yet, sadly, she notes that while these men seethe at us, women tend to show them misplaced sympathy instead:

Women are raised to be sympathetic, and protective toward the vulnerable, and there is something sweet, unexpected, and powerful about being a woman and sympathizing with a man not because he demands it but because you genuinely feel sorry for him, for his debilitating envy and his fear of discovery and his sense of powerlessness to live as he wants. The supermodel Heidi Klum and her crowd may feel sorry for helpless men, whipsawed by passion every night of the week but this is not a stance that society affords most women.

This double standard is clear to Bloom in the dynamic between one of the cross-dressers, Mel, and his wife, Peggy. Peggy is not only the director of the cruise but the spokesperson and model for the wives. Mel, meanwhile, is able to enjoy his carefree time as “Melanie” and even rely on his wife to watch his cholesterol intake. Bloom captures a particularly telling interaction between Peggy, Mel, and other cross-dressers.

One evening Peggy says, with a slightly pursed expression, "My next book is on joy: the difference between the level of joy that cross-dressers experience"--she holds her hand up over her head--"and the level of joy that their wives experience." Her hand drops to her waist. The cross-dressers around us say nothing. They nod, joyous astronauts sympathizing with the poor wives left behind and trying not to show how much better a time they are having. I think of the twinkle in Mel's eyes and the fact that nothing like a twinkle ever appears in Peggy's. It must be psychologically exhausting for her to turn this pain into a shared hobby, his compulsion into entertainment, his need into an occasion for celebration.

Bloom is also acutely aware that the twinkle in the eyes of the cross-dressers—like the one in the eyes of autogynephilic “trans women”—represents not merely the joy of taking part in a relaxing hobby but of acting out one’s sexual fetish in public. Replace the word “cross-dressers” in this next paragraph with “trans women,” “trans-identified males,” or “autogynephiles” and you encapsulate why people often feel uncomfortable around these men and why women in particular do not want them in our intimate spaces.

The greatest difficulty people have with cross-dressers, I think, is that cross-dressers wear their fetish, and the gleam in their eyes, however muted by time or habit, the unmistakable presence of a lust being satisfied or a desire being fulfilled in that moment, in your presence, even by your presence, is unnerving. The combination of the cross-dressers' own arousal and anxiety and our responsive anxiety and discomfort is more than most of us can bear.

At least when they were calling themselves cross-dressers, these men weren’t claiming to literally be women and clamoring for access to women’s washrooms, changing rooms, rape shelters, prisons, and sports. Even if they wouldn’t admit it was a fetish, at least they would admit that dressing up in women’s clothing was a leisure activity and not a “gender identity” that had to be protected by law.

How much has changed in two decades. Men with the same fetish as those in Bloom’s essay are now claiming to be female in droves. Their compulsion to act their fetish out publicly—which used to be mostly relegated to clubs, conventions, and cruises—has spilled out into every facet of life. While it used to be kept in check by a society that would reject and, if needed, ridicule the idea that a man was a woman because he declared himself to be one, the floodgates have opened, and nothing rushes faster than a man determined to fulfill a fetish he can finally act out with no shame.

As these men’s desire to be female is based on their very male, very heterosexual, and often highly regressive fantasies, it is no surprise that neither their wives nor Bloom were convinced:

These men are as far from being gender warriors and feminists as George W. himself. As one wife said to me, "For twenty years he couldn't help with the dishes because he was watching football. Now he can't help because he's doing his nails. Is that different?" For these men, the woman within is entirely the Maybelline version, not the Mother Teresa version, not the Liv Ullman version, and not even the Tracey Ullman version.

The saddest part, as Bloom noted above, is that women tend to meet this great insult by trying to be empathetic to these men. At the beginning of her article, when she writes that heterosexual male cross-dressers bother almost everyone, she also notes that is only women who support them.

The only people on whose kindness and sympathy cross-dressers can rely are women: their wives and, even more dependably, their hairdressers, their salespeople, their photographers and makeup artists, their electrolysists, their therapists, and their friends.

This is the situation we continue to find ourselves in today, with so many women giving away our spaces and our rights to appease a group of men who see them as nothing but narcissistic supply.

But the empathy you show to a narcissist will never be rewarded as you hope. If you step one toe out of line, try to set one boundary, or try to assert one difference between you as a female and your impersonator as a male, then you will feel his wrath. You get to exist as female while he can only pretend, and he hates it.

Great piece. The dots undeniably connect. For the conservative cross dressers among us, and I know three, today's transgender movement is a front row seat to most applauded gay conversion therapy they could ever have imagined.

This reminds me of Helen Boyd's two books: "My Husband Betty: Love, Sex and life with a Crossdresser" from 2003, followed by: "She's Not the Man I married: Life with a Transgender Husband" from 2007... a quick trip down a slippery slope.