Giving Birth and Men’s Appropriation and Silencing of Women

Disregarding all boundaries and limits

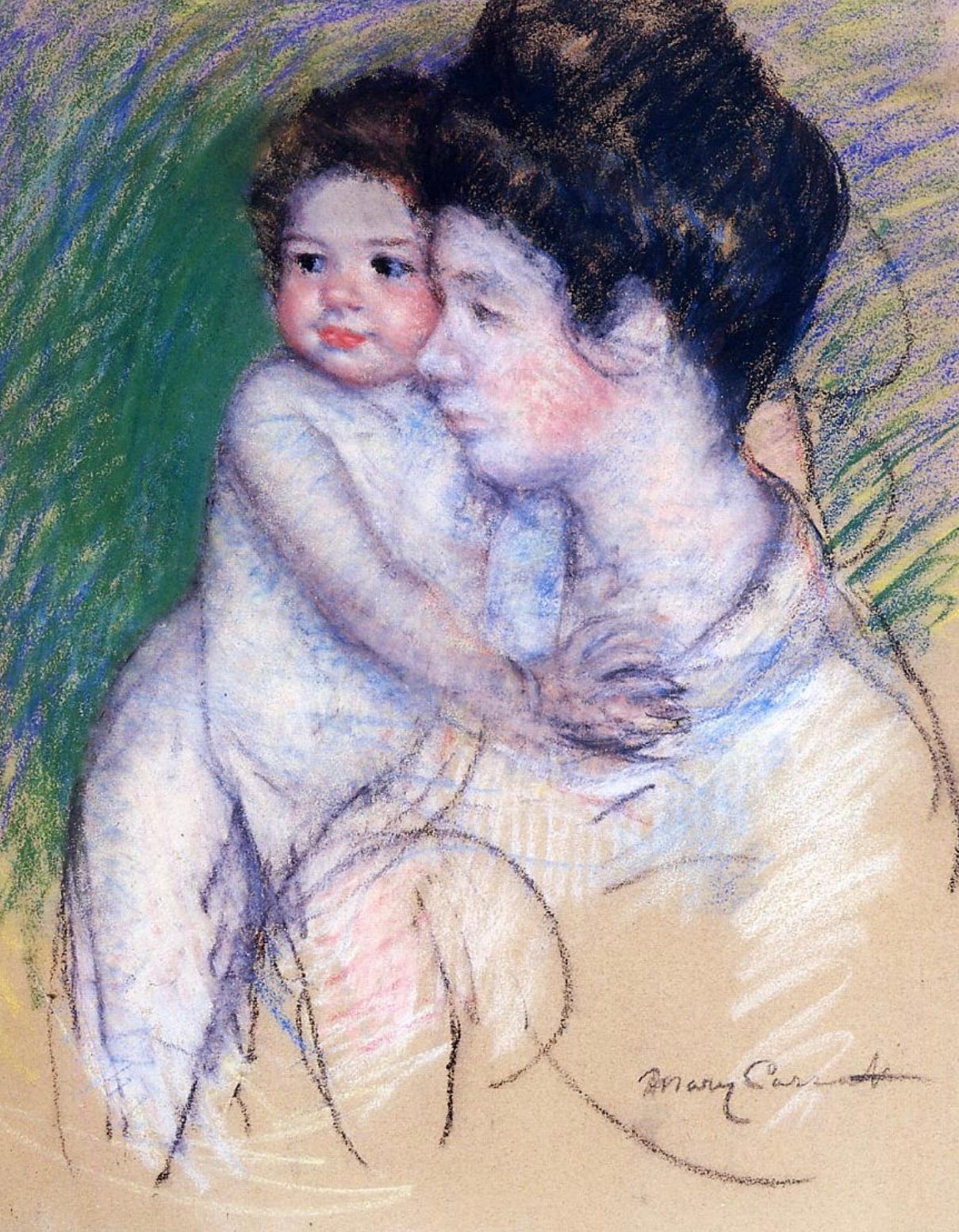

If we were not invisible to ourselves, we would see that since the beginning of time, we have been the exemplars of physical courage. Squatting in fields, isolated in bedrooms, in slums, in shacks, or in hospitals, women endure the ordeal of giving birth. This physical act of giving birth requires physical courage of the highest order. It is the prototypical act of authentic physical courage. One’s life is each time on the line. One faces death each time. One endures, withstands, or is consumed by pain. Survival demands stamina, strength, concentration, and will power. No phallic hero, no matter what he does to himself or to another to prove his courage, ever matches the solitary, existential courage of the woman who gives birth. (p. 63)

- Andrea Dworkin, “The Sexual Politics of Fear and Courage,” 1975, in Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics

But the distinguishing feature of man’s activities is that they have almost always been undert…