Pornography, Then and Now

Even at women’s expense, men’s sexual expression has been protected as what presumably secures women’s rights.

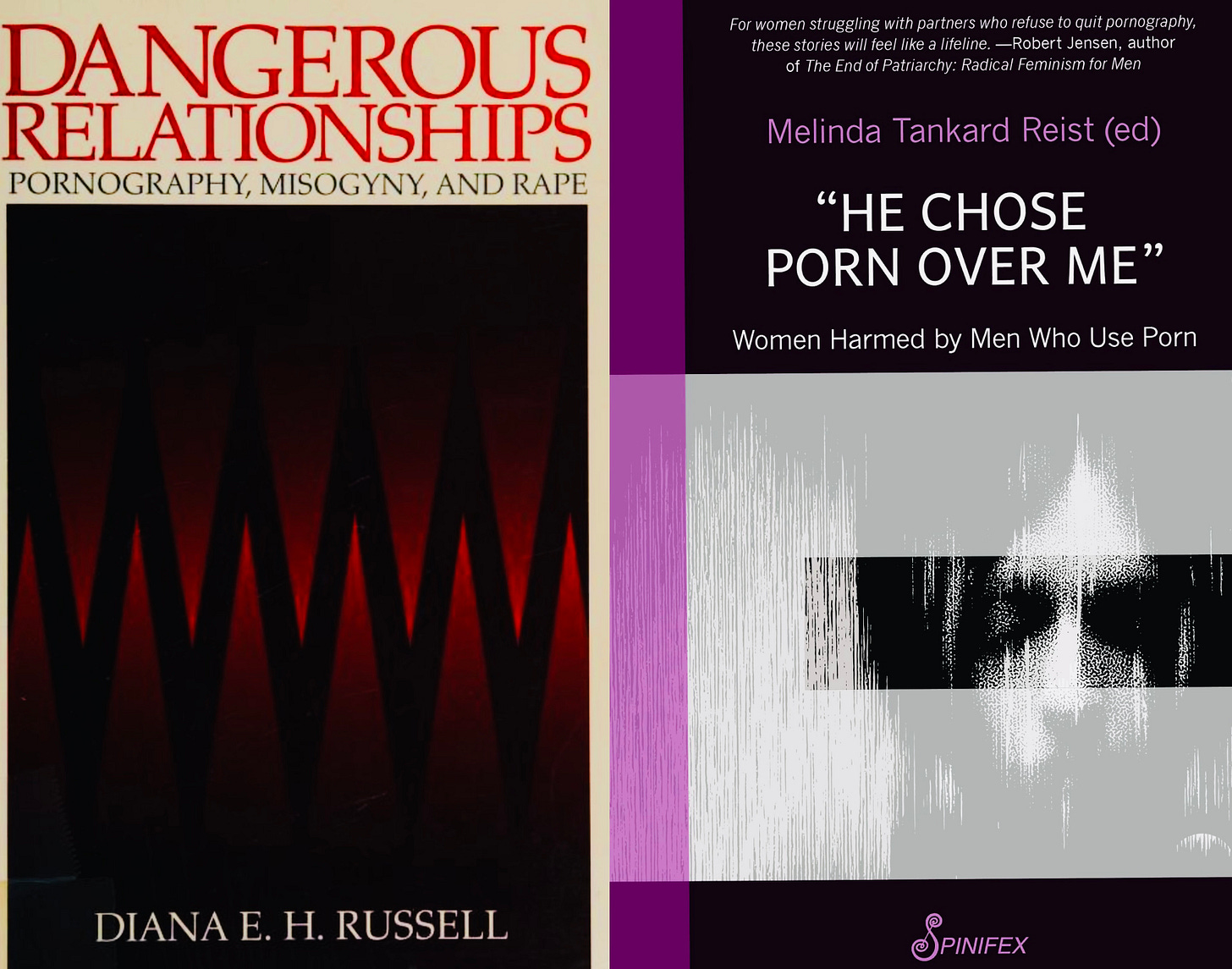

Born in 1996, I entered a world long saturated in pornographic images, where Hustler and Playboy propagated. Here I am not merely referring to just sexuality in any media, broadly understood, but rather sexuality coupled with heightened violence. And, further, the pattern in most pornography, that which drives the almost entirely male consumer base, has appeared to be male violence against women. “Sexy” defined by women’s degradation has defined prostitution and pornography as what Robert Jensen refers to as “the sexual-exploitation industries.” Present conditions of consumption differ from reading, say, either birth control material from Margaret Sanger in 1917 or D.H. Lawrence’s censored 1928 novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Recently, I had talked with the staff at The Distance about pornography and speech. In particular, we no…