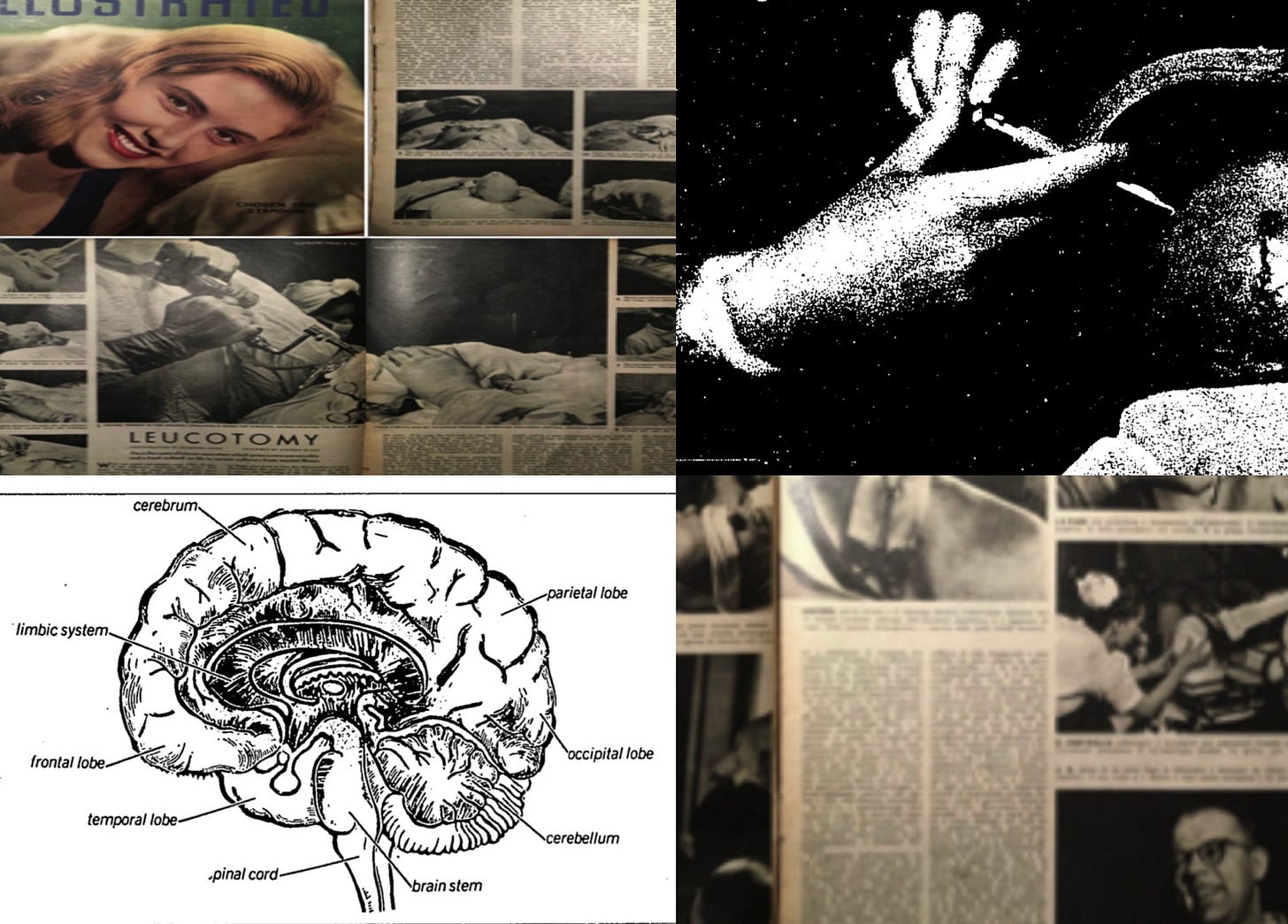

Psychosurgery, a Predecessor to ‘Gender-Affirming Care’

From “life-saving medicine” to medicalized dehumanization

Please consider subscribing and supporting our work at The Distance! We are thankful for any donations to support the writing and historical analyses. Our readers’ support keeps us going!

In one case, Dr. Andy removed a part of the brain of a 9‐year‐old hyperactive boy. The results of the first operation were not considered satisfactory, and several more such operations were performed. In the end, the boy’s hyperactivity was ameliorated, and Dr. Andy believes the operation prevented the child’s being kept under permanent sedation and restraint. But critics emphasize that the boy’s intellectual capacity deteriorated after the operations, and that—since some important brain development continues through childhood—the youngster never got his chance to learn what nature might eventually have done for him. It is mainly because of this uncertainty that Am…