The 'Gender Identity' Patent Medicine Show

An American tradition continues

Originally published 27 March 2023. Our subscriber list has grown by leaps and bounds since then and it has stood the test of time. WPATH files and disclosures, the Cass Review, and strong executive orders from Donald Trump all indicate that medicalized gender identity is a postmodernist form of patent medicine fraud.

Confidence trickery — fraud by deception — is ancient.

Magic is the original form of confidence art, and all confidence art derives from the performance of ritual magic in our distant past. As Rex Sorgatz writes in the 2018 Encyclopedia of Misinformation, the confidence artist must “tell a story that persuades the victim. And to persuade, you must become a convincing actor,” identifying and exploiting the weakness of the mark by incorporating it into the ritual. This is the real magic.

Everything depends on knowing what the mark wants, which is the same as knowing what they believe. We want to be fooled into believing what we already believe. “Because the mark participates in their own undoing, the con artist is sometimes referred to as the most noble criminal,” Sorgatz writes. “A good con man never forces you to do anything. He doesn’t steal; you give. Guns and violence are prohibited in most cons.”

“The only weapon is the story of the con itself.”

Or to use the postmodern term, what matters is the narrative. A story that resonates, that people are primed to believe. For example, if you want to peddle wrong-sex hormones, you might say: “I was born in the wrong body, and this explains everything about me and my life and my being and my purpose.”

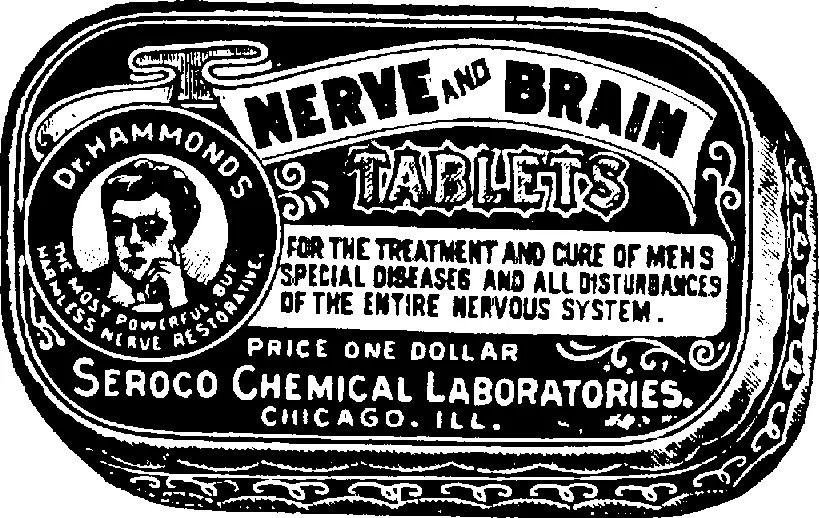

Gender identity is the new patent medicine show. Rather than callithumpian bands or ballyhoo, the charlatan of “affirmation” uses Tumblr and TikTok to draw their crowds on virtual streets. The story of the con is the only weapon they use.

“The charlatan achieves his great power by simply opening a possibility for men to believe what they already want to believe,” Grete de Francesco wrote.

In The Power of the Charlatan, de Francesco says that “the extraordinary power of impostors is therefore only to be understood after a consideration of the minds and circumstances of their gullible victims, the crowds who sought them out, half convinced before a word was spoken.”

To win over marks, a charlatan needs to know enough, but not too much, for they are a counterfeiter of knowledge, creating pseudoscience that suits the appetite of the mark. “The half educated wanted no really learned leader, nor would they listen to one wholly ignorant,” de Franceso wrote. “A half-educated man need not be a charlatan, but most charlatans have been half-educated men.” The trick is to sound confident in one’s own knowledge while speaking arrant nonsense.

For example: Abracadabra, some penises are female.

Or: Erasing the Jews from Europe will make Germany great again no matter how the war turns out.

Published in 1937, translated into English on the eve of World War II, de Francesco was really writing about Adolf Hitler. Arrested late in the war during the German occupation of Italy, she died in a concentration camp in 1945, a penultimate victim of magical thinking by large groups.

Occult practices were popular with many high-level Nazis. But such thinking is everywhere and rarely results in totalitarianism on its own. A smorgasboard of occult rituals has always been available in America, land of the free. Psychics and spirit mediums do a brisk business in cold readings across all 50 states, the inheritance of a nation that was steeped in religion from its inception. During the 19th century, everywhere former frontiers had become prosperous, Americans with disposable income and little knowledge of science made perfect marks. It was fertile soil for European confidence traditions to take root, share ideas with African and Native American traditions, and turn a great profit by fleecing the rubes.

Lawmakers in the English-speaking world responded to the harms of these trades long before the colonization of the Americas. As early as 1511, Henry VIII deplored “the science and cunning of physick and surgery, [that] is daily within this realm, exercised by a great multitude of ignorant persons, of whom the greater part have no manner of insight in the same, nor any other kind of learning.” So-called “quackbills” advertising medical services were among the first printed materials in London. Ben Jonson called the quack a “turdy-facy, nasty-pasty, lousy-fartical rogue.” They caused “grievous hurt and damage and destruction of many of the King’s liege people,” Henry declared.

Elite disapproval ended under Charles II, who issued the first royal patents for medicines. After that, the “pseudoscientific pitch was considered cultivated entertainment for the English aristocracy,” Anderson explains. With elites signalling acceptance, rogues were free to invent the modern sales pitch. English jurisprudence adopted the Latin term caveat emptor, “buyer beware,” giving victims of quackery no legal recourse.

These attitudes, along with “proprietaries” made from herbs, came across the Atlantic to help shape a new nation. Medicine men were among the most successful early immigrants, and patent medicines became one of the very first major industries in America; a young Benjamin Franklin advertised “nostrums” in his newspapers. Contrarily, scientific medicine was not yet scientific at all, and the educated physician was widely distrusted.

Samuel Lee Jr. was the first to patent his cures with the fledgling federal government in 1796. The new nation was thus born with an ethic of self-care, which solidified when herbalist Samuel Thompson was acquitted of murdering a patient who died of his “cure.” The Thompsonians, as his acolytes called themselves, claimed a populist mandate to “make every man his own physician” and “break down the aristocracy of learning and science.” Their weapon was a story: You are smarter than the fancy city boy with his Latin grammar.

By the 1880s, ads for patent medicines were painted on barns everywhere across the country. The most common product advertised in American newspapers was patent medicine, accounting for half of all their revenues, according to historian Ann Anderson in Snake Oil, Hustlers, and Hambones. This created an obvious conflict of interest. “Newspaper editors adopted a tacit policy of supporting the medicine industry, as they (or their publishers) were loath to criticize their most important source of income,” Anderson says. “As a result, the public was slow to learn about the dangers posed by many of the formulas.”

That dubious American tradition has continued with ‘gender medicine.’ The “psychology of the pitch is the same” on television as it was in newspapers, Anderson says. Most major media organizations still amplify spurious claims based on low-quality evidence: that puberty blockers are reversible, that sex change is literal and real, that hormones and surgeries can fix what is in a person’s head, that a man with “feminine” presentation is somehow less violent or dangerous than other men.

The story is the weapon, and a compliant news industry propagates that weaponized story at every turn, or goes silent whenever the facts clearly contradict the story. Male athletes cheat at sports and get fancy photo shoots on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Detransition rates and health risks are minimized. Dana Rivers murders two lesbians along with their adopted black son and gets a news blackout.

Worse, a new generation of crusading activist-journalists will move instantly to attack, defame, and try to destroy critics of the gender identity fraud. Thousands of clickbait articles have denounced JK Rowling for supposed transphobia. Taylor Lorenz doxxed Chaya Raitchik, the creator of Libs of TikTok, for the crime of reporting on gender identity groomers in schools. At least two newspapers have published spurious, single-source stories about Jamie Reed after she blew the whistle on the clinic where she worked in Missouri.

This is not quite totalitarianism. But with President Biden calling opposition to the sterilization of minors “almost sinful” and Democratic legislators passing laws to take children away from parents who don’t “affirm” their magical, mystical, invisible, suddenly-announced ‘gender identities,’ we are not very far from that point.

Their weapon is a story that people have believed because they wanted to believe it, that reinforces itself all the time. “Once you're within the trans community, your doubts get managed by everyone else,” detransitioner Michelle Zacchigna tells Michael Shellenberger.

I was told that everybody who identifies as transgender doubts that they're transgender at some point in time. They all have those doubts, but it's just internalized transphobia. You've internalized society’s idea that trans people are worth hating, and so you hate yourself. That's why you're doubting whether you’re really transgender.

The regular transition service was too onerous, wanting multiple appointments. But Zacchigna “had connections” to get “referred to a particular clinic that seemed comfortable bypassing that process. There wasn’t really any exploration of my distress. They just collected signed documents and did bloodwork.”

This is not medicine, it is magic. These are not doctors, either. They are sorcerers.

Showman P.T. Barnum identified Italian roots to American medicine shows, and since he ran one of the biggest medicine shows in the world at the time, he would know.

Our word “charlatan” comes from the Italian ciarlatano, “one who sells salves or other drugs in public places, pulls teeth and exhibits tricks of legerdemain,” Anderson writes. Another example of Italian influence is “Mountebank,” the Venetian term for “the one who jumps on a bench” to perform tricks, sell potions, and offer open-air dentistry services. “Zany” comes from zani, Italian for “clown.” Many clowns worked as assistants to these potion peddlers, bringing in crowds and praising the potion-master with stories of his successes. Jeffrey Marsh is a modern patent medicine clown; his act is over-the-top by design.

The English quack’s clown asistant was called “Merry Andrew,” commending his master to the crowd as a sage and scholar who had cured him of many complaints. Innumerable alchemists presented themselves as the High-German Doctor or the Italian Dottore. Convincing foreign accents made nonsense seem more plausible to “Enlightenment” Europeans, and later, Americans.

Fashionable hypochondrias, social contagion illnesses that the French called maladie du jour, bled over into the beginnings of mass consumerism. Indeed, “bleeding,” the infamous practice pioneered by Dr. Benjamin Rush that often killed patients who would have survived their actual ailments, was still being practiced with a lancet as the 19th century began. Americans thus rightfully distrusted doctors, who were not common outside of urban centers anyway. A culture of self-reliance inclined Americans to trust patent medicines over voices of authority using Latin terminology.

Understandably, the emerging modern medical profession separated itself from pseudoscientific quackery with increasing vigor during this period. Degreed physicians pushed for prohibitions on “quacking practices” such as advertising and discounting. Yet the relationship between medical science and quackery has blurred many times since then — and today, the profession is wholly complicit in the patent medicine fraud of gender.

Major medical organizations and publications once endorsed lobotomy on zero evidence. Today, the same organizations endorse pediatric transition with puberty blockade at Tanner Stage II, leading to sterility and lifetime medical dependence on exogenous hormones, again based on flimsy evidence.

Our maladie du jour is “gender dysphoria.” According to the British NHS, it is “a sense of unease that a person may have because of a mismatch between their biological sex and their gender identity.” This definition presupposes that ‘gender identity’ is a coherent phenomenon rather than an ephemeral state of mind, and this is supposed to justify medical interventions on the physical body of the sufferer.

The patent medicine believer falls into a predictable series of fallacies. First is the placebo effect, in which any supposed “cure,” even water or sugar pills, will seem to work. Compounding this, about 80 percent of all medical complaints resolve on their own, so if someone uses snake oil (petroleum jelly with camphor) and their gout improves naturally, the supposed patient will naturally credit the snake oil for their recovery.

Likewise, the sheer excitement of taking wrong-sex hormones often becomes “proof” that they are “working,” even as side effects begin to register. This is confirmation bias, which Sorgatz defines as “the overwhelming tendency to seek out information that conforms to existing beliefs while ignoring facts that contradict entrenched viewpoints.”

Because the snake oil has seemingly cured them, a user will actively work to reject evidence that the cure does not work, or is harmful. The only weapon used against them is the story of the con itself.

As Anderson explains, travelling 19th century patent medicine shows were the first American popular theatre. “Anything entertaining or attention-getting” — magic tricks, ventriloquism, melodramas, phrenology demonstrations, ghost stories, fairy tales, morality plays, the very first portable electric generators and lighting — “made its way into the medicine show platform.”

These mobile operators would try to squeeze as much profit as they could out of each locale, pulling up stakes and moving on to the next town before any locals got wise to the fraud.

American cities had standing “proprietary museums,” which Anderson calls “the perfect Jacksonian institution.” Unlike playhouses, these stationary medicine shows were not seen as immoral. Indeed, they often hosted Christian services. Barnum’s museum in New York had a 3,000 seat “lecture room” which he frequently lent for free to local ministers.

Like many “anatomical museums,” Barnum’s museum famously displayed grotesque “wonders,” many of which focused on disease. “Models of genitals eaten up by syphilis or gonorrhea were a special draw,” Anderson writes, because they carried an implicit moral narrative. Dime museums and penny arcades featured “the professor,” a figure “exuding authority and masking a lack of true erudition with bombast” who closed the medicine sales.

Many “cures” contained poisons. Chloroform, digitalis (foxglove), kerosene, strychnine, turpentine, and arsenic were often mixed with opium and its derivatives, such as morphine and heroin. Cannabis was another common ingredient. Along with herbs, emetics, and purgatives, these substances were always suspended in alcohol. Patent medicine makers insisted that the alcohol was vital to their formulations, but like the opiods, their true motive was to create a false euphoria in users.

“For a time, more alcohol was consumed in the form of patent medicines than in liquor,” Anderson writes. Temperance plays brought in large crowds, who then got drunk on the “cures” being sold without a hint of irony. Many became addicted. Whereas the patent medicine show had largely faded by 1920, Prohibition gave it new life as Americans got drunk on dangerous concoctions instead of liquor.

Religious overtones were always present in the medicine show. “The audience was put in the role of congregation: receptive and passive,” Anderson writes. “Quacks likewise had no compunctions about linking their pitches to religion.” Faith and fraud were “entwined in an odd yet profitable relationship” for most of the 1800s. According to historian Brooks McNamara, medicine pitches “were structured in exactly the same way as the presentations of tent evangelists.” The imitation was consciously done. Barnum “knew that evangelical Christianity was influential and he used the precepts of the religion to his own advantage,” Anderson writes.

By the Civil War, however, American clergy had begun to rail against the spiritual competition of this new sorcery. Human religious instincts were being misused and abused, leading the faithful into perdition. The Nation denounced Barnum in particular as “the personification of a certain type of humbug which, funny as it often appears, eats the heart out of religion.”

Stereotypes are stories that we already believe.

Patent medicine shows always trafficked in stereotypes. Stock characters in the shows played on every trope of foreign or exotic origins. Cures for “female trouble” invoked the Old Maid, the Suffragette, the Nagging Wife. Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which spawned many stereotypes of slavery, was produced everywhere on stage to sell patent medicine.

During that decade, “men with smudged faces and inside-out clothing, reminiscent of chimney sweeps and coal miners, were a precursor to the blackface minstrel clown,” Anderson writes. But the most common, and by far most successful, stereotype used to sell patent medicines was the “the romantic Indian who was in perfect harmony with the environment, never got an illness he couldn’t cure, and was the physical and spiritual superior of the white man.” This American version of the ‘noble savage’ was a common medical trope during the 19th century, for “sincere health practitioners as well as hucksters used the repute of Native Americans to drum up business,” Anderson says.

William Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill, was one of the most successful examples, but he was not even the most famous in his own time. Forgotten today are John Healey and Charles Bigelow, New England patent medicine charlatans who invented Kickapoo Buffalo Sagwa in 1881. Employing hundreds of real Indians at a time, they presented an elaborate stage show, including a scene in which westward settlers get massacred. Their products “to clean and purify your blood” became the most successful patent medicine brand in America during that period.

The very last big patent medicine brand played on stereotypes associated with “hoodoo,” an American system of folk magic that is cousin to voodoo. Dudley J. LeBlanc, a Louisiana Cajun, “transformed the Bible Belt into the Hadacol belt” and made $24 million per year, a huge fortune in 1951. Free of outright poisons, Hadacol contained B vitamins and 12 percent alcohol, so it was often sold in shot glasses and in cocktails.

What made LeBlanc an innovator, though, was his solicitation of testimonials from consumers. Hadacol users claimed it had cured everything under the sun, including cancer. A team of employees would record the customers, talk to neighbors and relatives, and scrupulously document these “cures.” The testimonials “made good advertising copy, and were also a clever way to get around governmental restrictions on fraudulent claims.”

Sexist stereotypes are the secret sauce in the “mob hypnotism” of the 21st century patent medicine show. Girls who cut their hair short are ‘boys,’ while boys who like their hair long are ‘girls.’ Boys who play with dolls are ‘girls’ while girls who play with trucks are ‘boys.’ This is nonsense, of course, but it is a story that people already believed. “Influencers” are the new shills, touting the supposed hormone cure as the perfect panacea for every form of distress, providing the “social proof” that it “works.”

None of it is really original to them.

Profit is a matter of supply and demand, so manipulating the supply to create a perception of rarity made the patent medicine seem even more valuable. Pitchmen have always understood this: Get it now, folks, while supplies last! Take advantage of this EXCLUSIVE discount offer! The style continues through the infomercial and television shopping channels.

Likewise, every time a state legislature bans pediatric sterilization, transgender advocacy blares the siren for Armageddon. ‘Trans people’ are presented as the ‘most marginalized community,’ constantly threatened by people who want to extinguish it. “You don’t want us to exist,” the activists whine, complaining of “actual genocide” being committed against them, as if they were Jews in a death camp.

The net effect is to make their product — “gender transition” — seem rarer, and harder to get, and thus more valuable. In turn, this justifies every conceivable emergency measure. Democrat-controlled legislatures pass sanctuary laws enabling Munchausen parents to flee to their states in the middle of a divorce. Freedom of speech has become passé because misgendering supposedly causes lethal harm. Schools that would never dare keep anything else secret manage to justify hiding a “trans identity” from parents.

That last example plays on the most negative stereotypes of parental authority. Under the rubric of ‘gender identity,’ parents who fail to affirm their ‘trans child’ are evil, right wing, conservative, cisheteropatriarchal monsters — the sort of parents who would have tried to convert a gay or lesbian child, once upon a time. Never mind that most parents of “trans kids” are in fact liberals, or that their kids are most often LGB when allowed to grow up as normal. Once any parent stands in the way of transition, they become the parents who just don’t understand.

“People like to be consistent, even if it produces a foolish result,” Anderson writes. The gender identity patent medicine fraud pretends to be consistent with the experiences of LGB youth in the past, ‘a new kind of gay.’ Too many react accordingly, for they think they already know this story, and the stories behind the story.

Now that trans-virtuous and trans-credulous trans allies are losing their minds over the Commander-in-Chief's decision to assess whether the cross-dressing fetishists who pose as women are sane enough to serve in the armed forces, here's a question about the topic of trans in the military.

Of all those brave trans people who have volunteered to serve their country, what percentage of them are trans men? How many of those spunky, badass young women who've cut off their tits and are high as a kite on "T" have enlisted? How are their mastectomy scars going over in the barracks? How safe do they feel around all those strapping 19-year-olds in the shower room?

If trans were real it would be evenly distributed between men and women, and you'd expect rates of trans enlistment to mirror the rates among real women and men.

The answer is probably out there somewhere.