The Mattachine Society and the Question of Gay Assimilation

Two roads diverged in the movement

This post will be locked for one week.

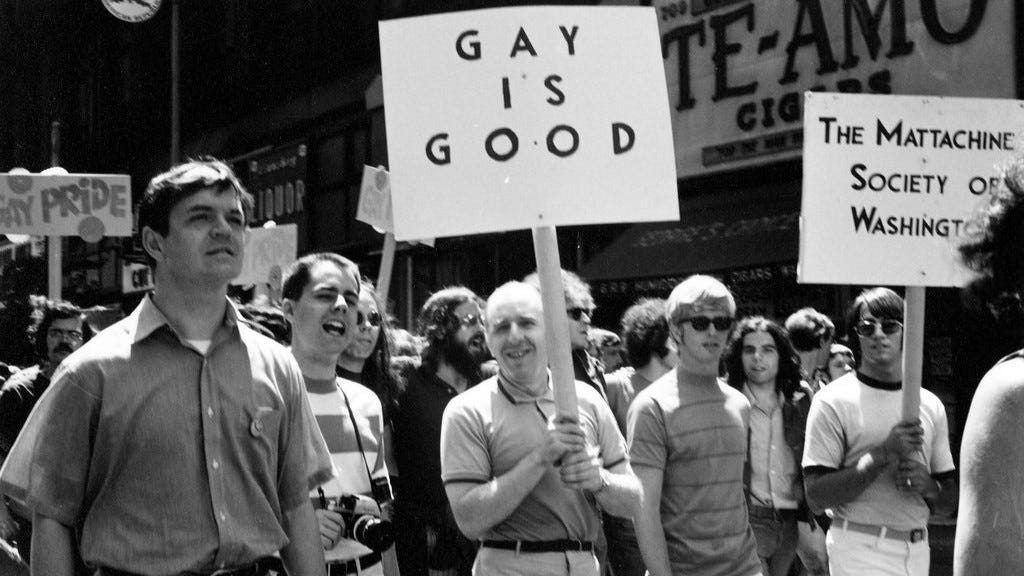

The gay rights movement didn’t start with Stonewall. Many actually trace its beginnings to the founding of the Mattachine Society in 1950. Even then, the Mattachine Society wasn’t the first group of early gay rights activists, but it did become the first such sustained organization in a long line of covert societies that stretched back to the 1920s in the United States.

In contrast to the idea of pride as protest, the Mattachine Society came to be known as an organization that sought gay assimilation and integration into society by working within existing power structures instead of tearing them down. The goal was to change public perception and thereby law and policy.

Naturally, this attitude and approach doesn’t sit well with today’s “queer” commentators. Writing for The Washington Post, trans activist Evan Greer complained that the Mattachine Society “actively discouraged members from engaging in ‘deviant’ expressions of gender and sexuality” and that “rather than challenge the rigid and repressive gender roles of postwar America, they embraced them in the interest of political gain.”

Well, yeah, the Mattachine Society wasn’t exactly interested in faffing around with “gender,” which wasn’t even conceptualized at the time as gender ideality activists conceptualize it today. It was started by gay rights and labor activist (and avowed communist) Harry Hay, along with some like-minded friends, with the specific goal of ending discrimination and improving the rights of gay men. The name was inspired by the secret medieval French Societé Mattachine, a fraternity of unmarried masked male dancers who satirized social conventions.

I can’t even be upset that such an organization, which championed a specific goal for a specific group of people, didn’t include lesbians (though a similar organization for lesbians, The Daughters of Bilitis, formed in 1955).

Hay himself was a provocative figure who initially envisioned the Mattachine Society as a more radical group. He even organized it according to the structure of the communist party, with an anonymous leadership order whose names were unknown to the rest of the membership. However, things began to change fairly early on in the organization’s history.