Transitioning but Not Transcending: Dispelling the Distortions of Andrea Dworkin’s Work

Part I of a series

A shortened version of this essay series appeared in a post to the Andrea Dworkin Archival Project Facebook page on March 23, 2023. However, based on multiple comments received, I have edited the original thoughts to clarify my points. I am taking great care with each source.

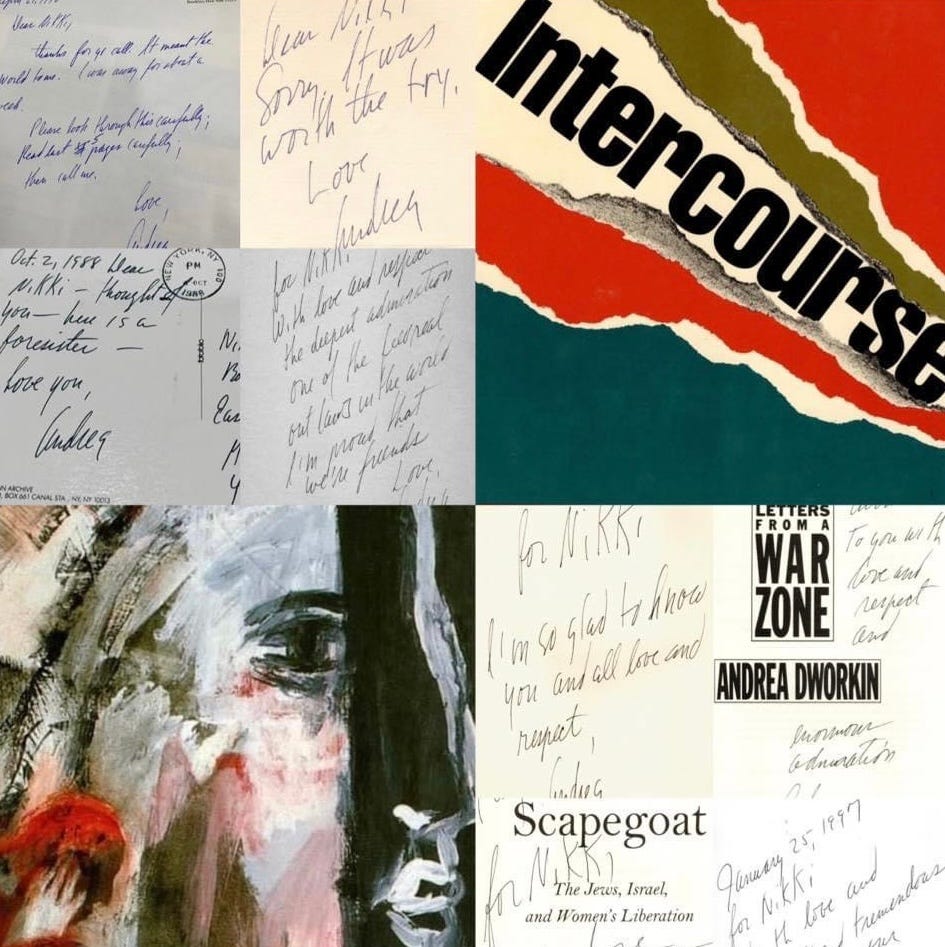

The present analysis reorients the focus, as the initial thoughts began with a discussion of John Stoltenberg’s The End of Manhood: A Book for Men of Conscience, first published in 1993. My reasoning for the previous thoughts regarding Stoltenberg was because Nikki Craft suggested we could make a post that talked about a certain excerpt Stoltenberg had sent her in 1997. The excerpt was titled “What Should a Man of Conscience Do When He Fucks Up?” Looking at that excerpt, we thought it was both interesting and ironic, given certain peculiar things Stolt…